‘Ink & Rebellion’ exhibit offers a journey through a timeline of censorship

September 28, 2023

“Ink & Rebellion: The Evolution of Censorship in Comics” features VCU Libraries’ world class Comic Arts Collection through the lens of suppression and control of creative content.

With significant collections of comics and graphic novels and a focus on histories of and stories by marginalized identities across all of its collections, VCU Libraries’ Special Collections and Archives is uniquely situated to establish a timeline of comics censorship. “Ink & Rebellion” traces a history of censorship in comics, from the establishment of the Comics Code Authority to the rise of underground comix, criminal censorship cases, challenged depictions of real-world events and contemporary graphic novel bans.

The exhibit, in the fourth floor gallery at James Branch Cabell Library, is on view during library hours throughout the fall semester. It opens Oct. 2 as part of Banned Book Week activities. Items on display are part of the larger Comic Arts Collection housed in Special Collections and Archives at VCU Libraries and are available for viewing and research.

“It's always worthwhile to discuss censorship, but this year the most challenged book in the country is a graphic novel, Gender Queer, so it is especially important to look back at history and see how we got here and what led to this current state,” said Special Collections and Archives Teaching and Learning Librarian Katharine Buckley. “Currently, we're witnessing a wave of challenges and bans in schools and public libraries across the country that target books, claiming material is inappropriate for young readers. These are similar claims that have been levied against comic books and graphic novels for the past 70 years.”

Along with Buckley, curators were Research and Collections Specialist Caroline Meyers and Processing Archivist Jessica Johnson with assistance from student intern Heather Riley Winn. Exhibit design was by Research and Collections Specialist Sarah Clay.

The exhibit may inspire viewers. “I hope students and visitors draw connections between the experiences they've lived through to the past and that they feel inspired to learn more, create art, or fight against censorship in their community,” Buckley said.

Some highlights of the exhibit

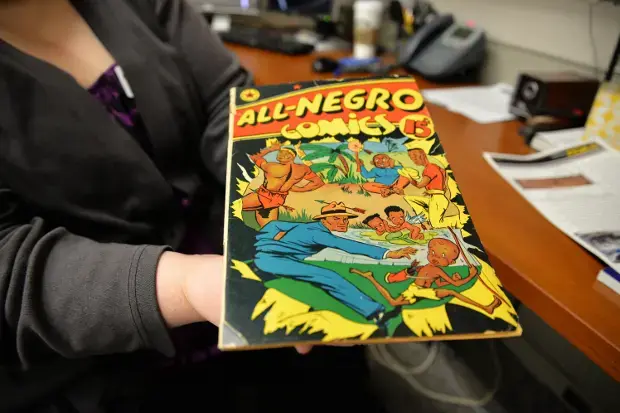

- One of the most significant holdings in VCU’s Comic Arts Collection, All-Negro Comics #1, was indirectly but effectively censored. Pioneering newspaper reporter Orrin Cromwell Evans created the comic book with partners and published it in 1947. The 48-page anthology comic is known not only for being the first comic by African-American creators, but also for its positive portrayal of African-American characters — such as detective Ace Harlem and Lion Man, a college-educated, scientist superhero — in an era in which most African-American comic book characters were racist caricatures. A second issue was planned and the art completed, but when Evans was ready to publish, no newsprint vendors would sell paper to him. He deduced that pressure had been placed on newsprint wholesalers by bigger comics publishers who came out with their own competitive titles centered on Black Americans.

- One of the most successful comic book companies was Entertaining Comics (EC Comics), specializing in horror, crime, science fiction, and satire comics, such as Tales from the Crypt and Mad. Their stories often had shock endings and addressed progressive themes such as racial justice, nuclear disarmament and environmentalism. EC Comics were also some of the most controversial, and by late 1940s, they and other comic publishers had come under scrutiny.

- In the 1950s, a nationwide moral panic brewed as parents grew concerned about the violent and sexual imagery in comic books. Concerns reached a head in 1954 when psychologist Frederic Wertham published Seduction of the Innocent, naming comic books as one of the chief reasons for juvenile delinquency. That same year, Congress convened a hearing, requiring comic book publishers to defend themselves.

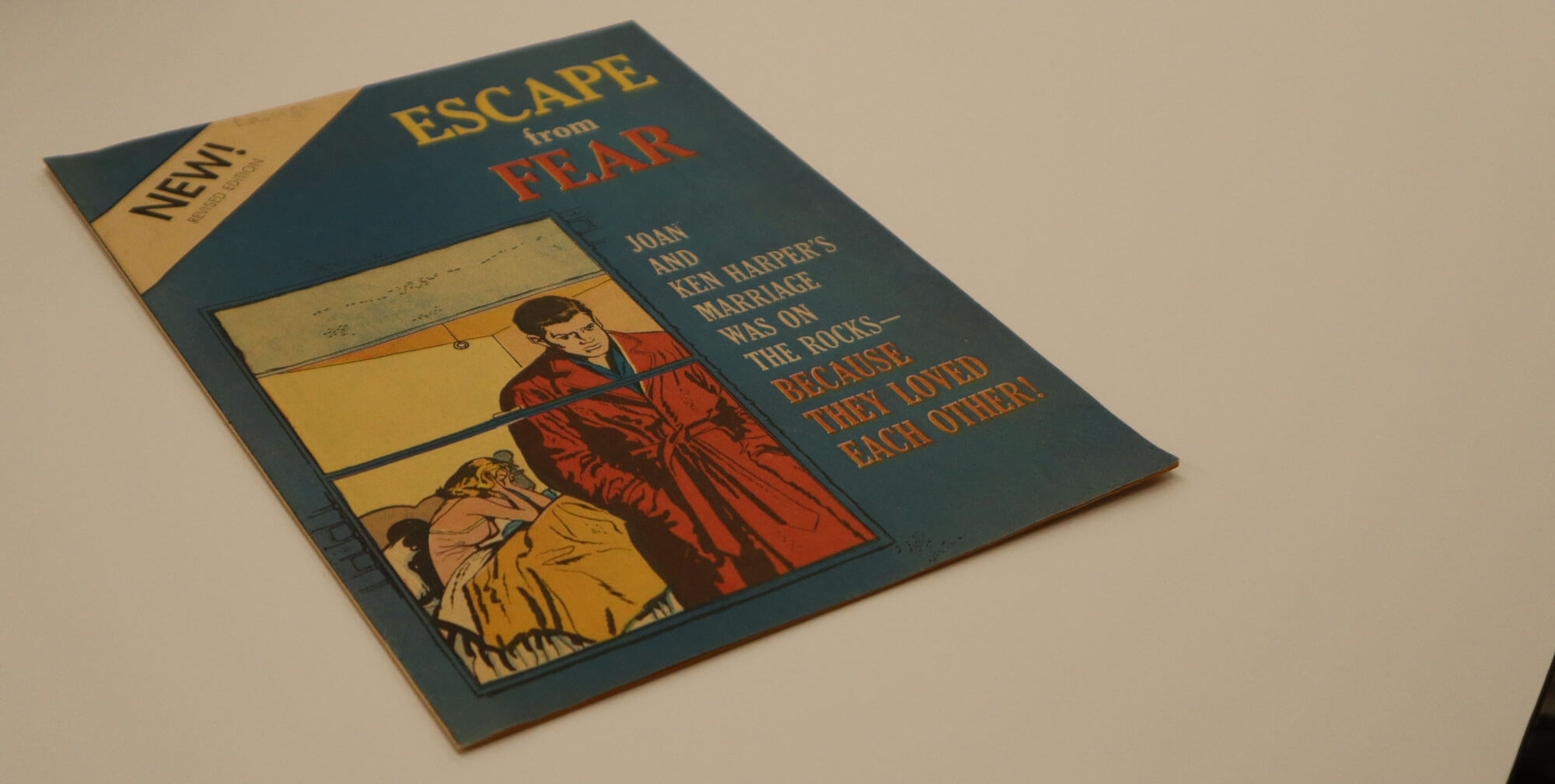

To avoid government censorship and address plummeting sales, in 1954, The Comics Magazine Association created the Comics Code Authority, a form of self-censorship. The comics that continued to be successful post-Code were kid-friendly. The Code’s restrictions on popular genres like horror and romance and the limitations it imposed on villains in superhero comics resulted in an industry dominated by lighthearted themes.

The words “horror,” “terror,” and “weird” could not be used on covers, a direct attack on EC’s popular titles. By 1956, EC abandoned comic book publishing rather than bend to the demands of the CCA, but it continued to publish Mad since its magazine format allowed it to sidestep censorship rules.

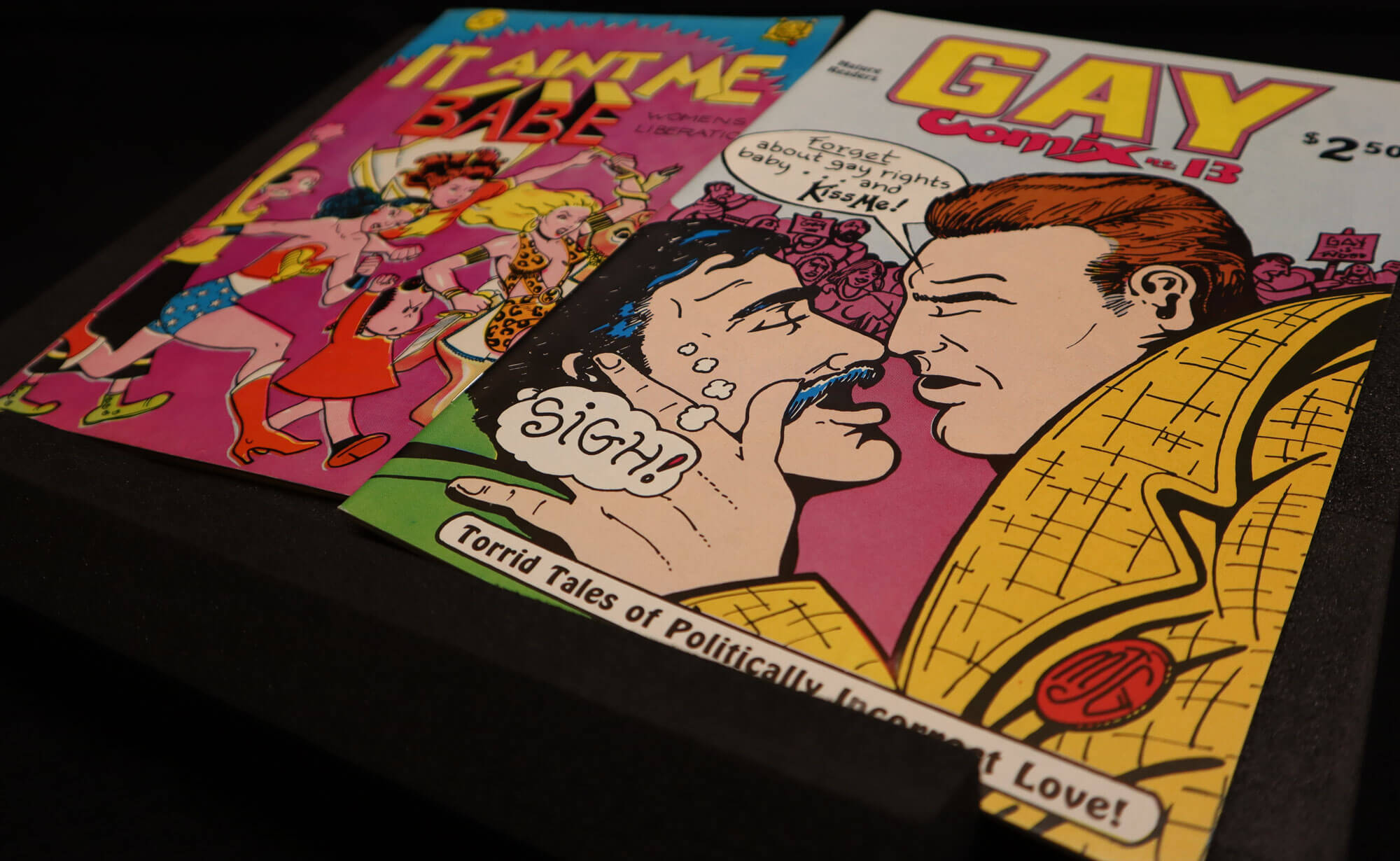

- Restricted by the Comic Code Authority from producing the content that defined them, some publishers went underground. A group of artists in San Francisco began creating their own comics in the 1960s-1970s. These underground comix were far outside the mainstream industry and thus free of censorship. Many of the comix depicted X-rated content such as drug use, sex and violence.

Underground comix grew in popularity and influence, representing a spirit of rebellion that was growing in the U.S. However, some underground artists, such as Robert Crumb, were determined to break any and all taboos and social norms. As a result, some material was irreverent to the point of depicting gratuitous violence, racist stereotypes and homophobic caricatures.

Underground comix broke many barriers in the medium: the first comic book created entirely by women, the first titular Black superhero, and the first gay and lesbian comic books.

- While the underground scene allowed comic creators to skirt the content guidelines of the Comics Code Authority, comics were still subject to the laws around distributing obscene material. The definition of what content qualified as obscene became more subjective after the 1973 Miller v. California Supreme Court case. Believing that comics were still for children and should reflect child-appropriate themes, law enforcement began prosecuting creators and sellers for obscenity. Underground and alternative comics, like Wimmen’s Comix and Zap, were targeted. The Comic Book Legal Defense Fund (CBLDF) formed in response to legal charges and provided support to cartoonists whose first amendment rights were challenged. The CBLDF still operates today, working in and out of the courts and advocating for comics in general.

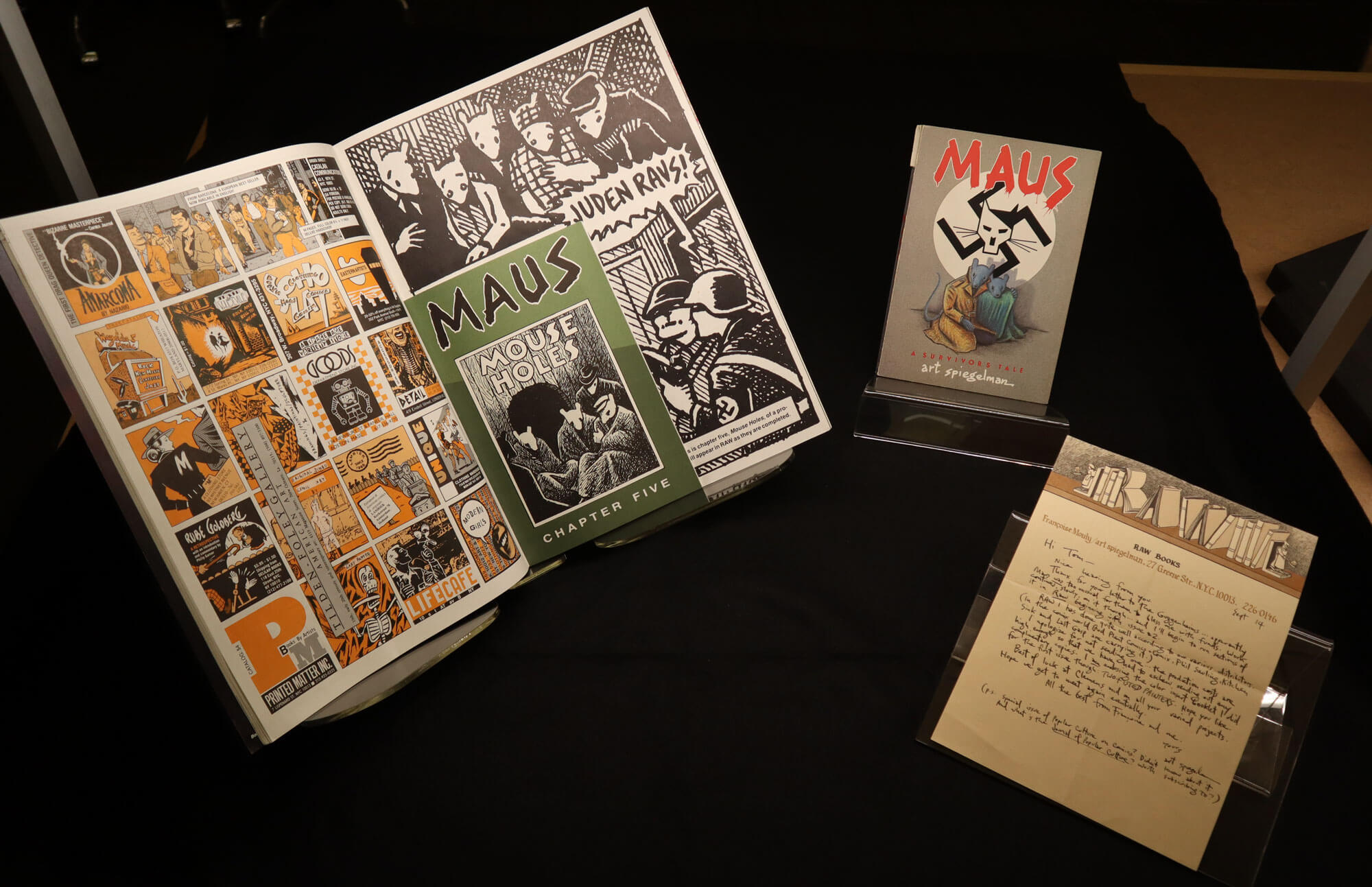

- Self-publishing allows artists more freedom and frees marginalized creators to share their direct perspectives. One of the most celebrated graphic novels printed started as an alternative. Françoise Mouly and her husband, Art Spiegelman, set up a printing press in their studio apartment, and began publishing alternative comics and books. They published Raw Magazine, a comic anthology featuring work from cartoonists who had no other opportunities for publication, from 1980-1986. Raw is where Spiegelman’s Maus was first published. Maus, Spiegelman’s autobiographical work about his parents’ experiences surviving the Holocaust, was published chapter-by-chapter through Raw. Spiegelman self-published his work while he struggled to find a publisher for the full book-length work. Eventually, Maus was compiled into a single graphic novel in 1986 and received unprecedented praise for a work of comics art. It became the first graphic novel to win a Pulitzer Prize.

One of curator Buckley’s favorite discoveries in working on the exhibit was finding a letter from Spiegelman in the Thomas Inge Papers. In that letter, Spiegelman discusses the struggle to get funding to work on Maus and the decision that he will self-publish Maus chapter-by-chapter in the comics anthology “Learning that the origins of such an important, popular work are rooted in the tradition of alternative publishing is amazing to me,” she said.

Maus is often used to introduce young readers to the Holocaust. As Maus has risen to prominence, it has also been subject to bans and challenges. In 2022, a school board in Tennessee voted unanimously to remove Maus from its curriculum. Maus has also received international censorship through bans and book burnings.

- Content at risk of censorship or challenges can include social critique or materials designed to raise social awareness. Examples in the exhibit include Keiji Nakazawa, who is best known for his manga Barefoot Gen, a lightly fictionalized saga depicting the U.S. atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Before Gen, Nakazawa drew the one-shot manga, I Saw It, of his experience surviving the bombing. In the 1980s, Leonard Rifas of EduComics published Nakazawa’s work, the first full-length manga to be translated and distributed in America. Struggling to build an audience for the anti-nuclear comics, Rifas never sold out the first printing.

- Lyn Chevli and Joyce Farmer began work on the pro-choice comic Abortion Eve before Roe v. Wade legalized abortion in 1973. A one-shot exploring the process of seeking an abortion through conversations among women characters rife with questions and anxieties, the content of Abortion Eve fell under the definition of obscenity at the time. Abortion challenges reoccur in the U.S. today, rendering reliable information about reproductive health care more precarious.

- Graphic novels are popular censorship targets for representing sexual or violent images and discussing difficult historical topics. Graphic novels about the LGBTQ+ community or involving LGBTQ+ characters face additional scrutiny. These challenges are predominantly brought by conservative groups who find LGBTQ+ themes inappropriate or offensive.

Want to explore VCU Libraries' Comic Arts Collection?

Search VCU’s Comic Book Index. To view items in the Comic Arts Collection, visit Special Collections and Archives on the fourth floor of Cabell Library. The department is open Monday–Friday, noon to 5 p.m. Walk-ins are welcome and appointments invited. To make an appointment for research help or to see particular items: (804) 828-1108 or libjbcsca@vcu.edu.

Chat

Chat